Hearig the Same Record Over and Over Again

Repeat After Me: It'due south Normal to Play the Same Song Over and Over Again

Failed to save article

Delight try over again

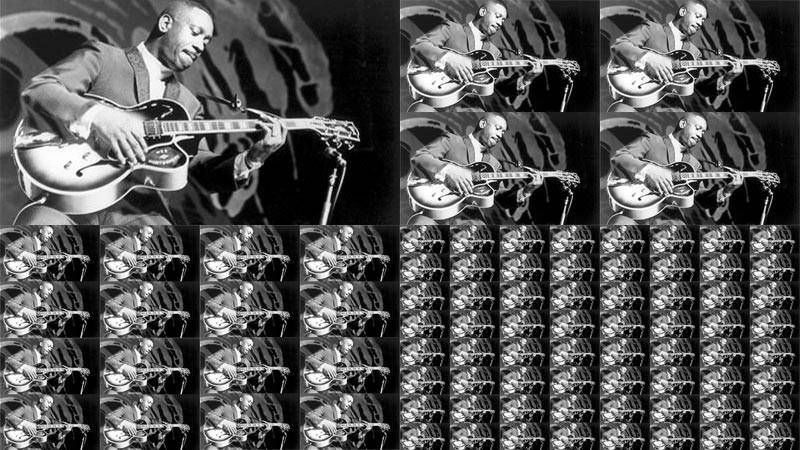

Why wouldn't ane listen to the brilliant jazz guitarist Wes Montgomery on repeat? (Prototype alteration: Gabe Meline)

"Dad, can you please play another song?"

The asking came on a recent Dominicus morning from my fourteen-year-onetime son, every bit I was in the kitchen listening for the 12th straight time to Wes Montgomery'due south 1965 recording of John Coltrane'southward "Impressions" -- a whirlwind of sensational guitar playing, complemented by bass (Arthur Harper), pianoforte (Harold Mabern), and drums (Jimmy Lovelace) that lift Montgomery's chords into the sonic stratosphere.

Just this gem of musical dervish-ness -- Montgomery and jazz at their all-time -- is simply 3 minutes and 37 seconds long. I want the song'due south feeling to terminal much, much longer. And I have the power to practise that, by changing the YouTube URL just a tiny bit. In a few seconds, I've allowable my reckoner to repeat the song ad infinitum.

I've listened to Montgomery'due south Impressions recording for equally long equally an hour directly, usually as I write articles. The menstruum of words, and my concentration and energy levels during the process, are much, much meliorate for it.

But information technology raises ii questions: Am I disrespecting Montgomery's original 1965 performance by using it as a kind of background music? And is it cognitively normal -- non to mention socially normal -- to listen to so many songs (from Natacha Atlas' "The Righteous Path" to the Super Rail Ring's "Republic of mali Cebaolenw") on repeat, twenty-four hour period later day subsequently day? For the latter question, I consulted On Repeat: How Music Plays the Mind, a 2014 book past Academy of Arkansas professor Elizabeth Hellmuth Margulis, who directs the school'southward Music Noesis Lab. What I found is that yes, information technology'due south normal. Perfectly normal. And the more I study the issue, the more I detect people with whom I take this "musical repeatism" (my phrase) in mutual.

Usually, they're what I'd call "creative types," every bit with architect Zaha Hadid, who before her death in March told the BBC's Desert Isle Discs plan nearly her propensity to play films and songs on a loop while she painted and did other work. Amongst her favorite repeated films: American Gigolo, the 1980 movie starring Richard Gere as a high-paid escort. "Unfortunately," Hadid said, "I get stuck on ane thing; for case, music. I like one song, and volition play it over and over once more, like forever, until I absolutely can't heed to it anymore."

And so for Hadid, familiarity ultimately breeds antipathy, a bicycle that Margulis touches on in On Repeat, when she writes that re-listening to songs "increases pleasure for a certain menstruum and then reduces information technology. The human relationship between exposure and enjoyment, in other words, is nonlinear."

In nonetheless other words: Repeated songs tin be like a quick affair. Intense. Personal. Pleasurable. Over. But that'south non quite correct for me. The affair never really ends. It's only on pause, until y'all're in the mood once more. And and then the relationship begins afresh. My human relationship to repeated music centers on the trance-like state that information technology puts me in. Repeated songs help me focus. They elevator me into a college state of consciousness, accentuating the physical state that's often needed to create something on a blank canvas. On repeat, the right songs (like Mazzy Star's "Fade Into You") can also tiresome me to a meditative land. Equally Margulis puts information technology in her academic way, repetition has a manner of "fostering an intimate connection to the music while bypassing conceptual noesis and allowing the audio to seem 'lived' rather than 'perceived.'"

Musicians themselves, of course, dwell in the world of repetition. "Impressions" relies on a repeated two-notation piano pattern that anchors the song at the beginning and the end. Coltrane borrowed that pattern from Miles Davis' 1959 song "So What," from Davis' Kind of Blue album, on which Coltrane was integral on saxophone. As jazz scholar Lewis Porter has observed, Coltrane's original "Impressions" too repeats a musical theme that'due south very similar to 1 institute on composer Morton Gould'southward 1939 song "Pavanne."

Merely repetition can be a contradiction both for musicians and those of the states who listen on repeat. Many musicians, peculiarly as they get older, don't like playing their big hits over and over once again. Miles Davis hated information technology. Coltrane's whole career was nearly pushing forward -- non looking back and repeating songs like "Impressions." In his book How Music Works, David Byrne of Talking Heads speaks for many celebrated musicians when he says, "We don't want to be stuck playing our hits forever, merely merely playing new, unfamiliar stuff tin can alienate a crowd -- I know, I've done it."

Notwithstanding, Byrne speaks of the public space where musicians and fans intersect. My repetition exists, thank you to headphones, mainly in a individual space, where the repetition is mine and mine lonely. On those rare instances when I listen without earbuds, my musical repeatism becomes an effect. To me, the practice is less obnoxious than headphone listeners who sing desperately and off-key equally they repeat the words of their favorite songs. I want nothing to do with that kind of repeatism. Good repeatism is a thing of utter beauty. Andy Warhol'southward Eight Elvises and Campbell's Soup Cans are visual allures because of their repeated motifs. In How Music Works, Byrne traces the history of "encores" to the 18th century -- to the Italian opera house La Scala, where sometimes-unruly crowds would yell for the performers to come back and play another song. In the timeless film Casablanca, Humphrey Bogart'southward angry, drinking character has to plead for his pianist to repeat "As Time Goes By." None of usa have to plead and yell anymore -- and certainly not in public.

Rather than breeding contempt in music, familiarity breeds comfort. In On Echo, Margulis cites another professor'south calculated interpretation that "99 percentage of all listening experiences involve listening to musical passages that the listener has heard earlier." None of u.s.a. want to be Sisyphus, repeating the aforementioned chore over and over again. None of united states want to listen to one song for the residue of our lives. But none of us want to hear "I love you" just once, either. In the right relationship, we desire to hear it again and once again, 24-hour interval and night. Repeated songs have a positive effect on the encephalon; they're a mail service-modernistic phenomenon that produces ecstasy on demand. "Encore" becomes automatic.

Websites now exist to document the waves of repeated music that people heed to. These songs are the tracks of our lives, letting everyone know that "musical repeatism" is alive and well. Information technology was always there, of form, simply now information technology's an embedded role of the civilization that is as public as we want it to be -- a selective trait that allows repeating a vocal to accept the states higher and higher until we're high enough to stay. When we come back down, we're ready to repeat another song. Over and over again.

Care nearly what'southward happening in Bay Area arts? Stay informed with one electronic mail every other week—correct to your inbox.

Thanks for signing upward for the newsletter.

Source: https://www.kqed.org/arts/11523994/repeat-after-me-its-normal-to-play-the-same-song-over-and-over-again

0 Response to "Hearig the Same Record Over and Over Again"

Post a Comment